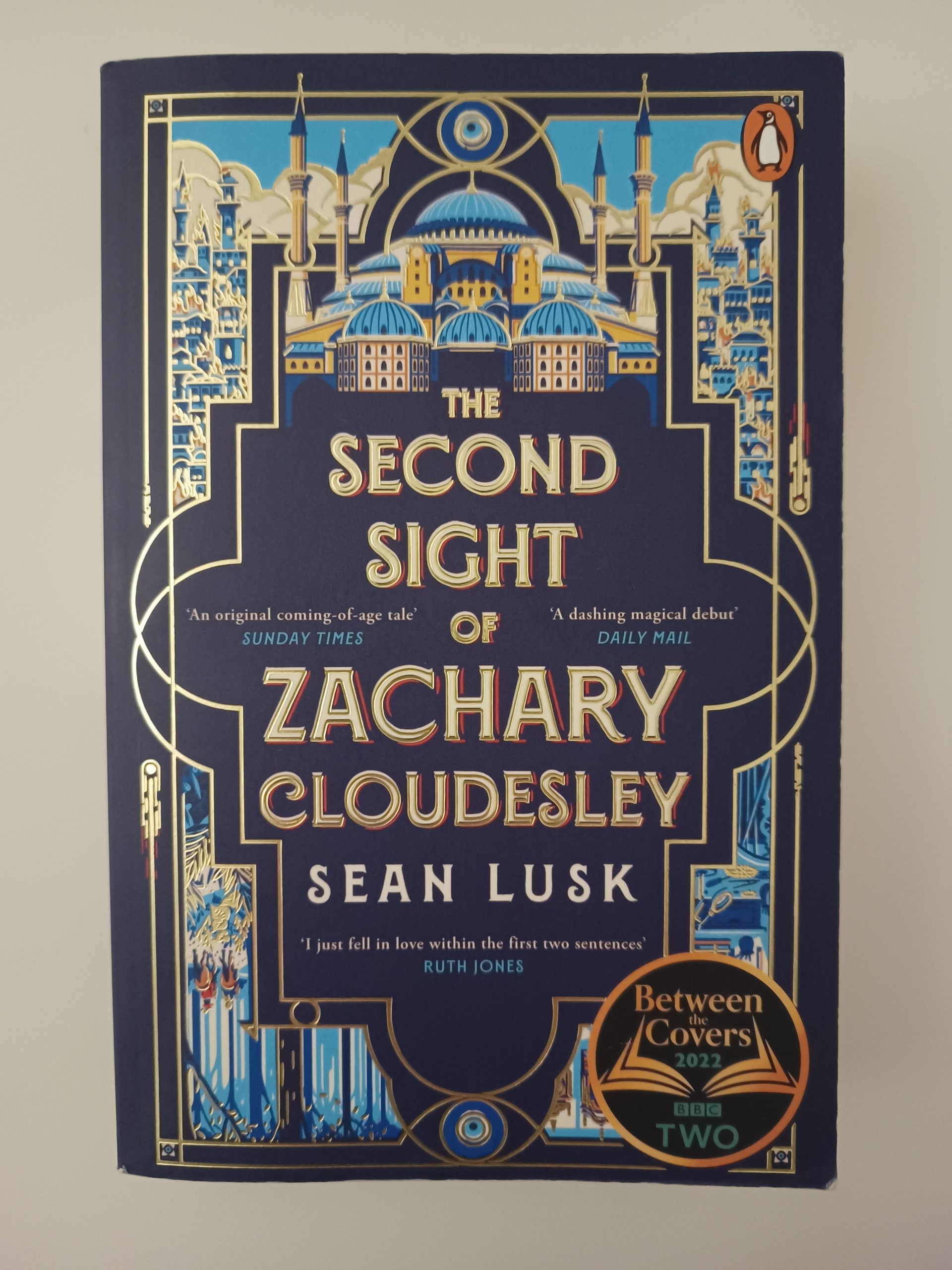

The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley, by Sean Lusk

The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley: before even opening the book, I was intrigued by its title. As titles go, it's rather cryptic - even a little eccentric - but its words roll beautifully off the tongue and it has an undeniable allure. As I read the book, I discovered that these qualities of the title resonate throughout Lusk's whole novel: this is a unique book full of charming quirks, set in a world both fascinating and beguiling, and told in absolutely beautiful prose. I liked it. This review details why.

The tale begins in London in the 1750s. The eponymous Zachary Cloudesley is a child, growing up in his father Abel's clockmaking workshop. Zachary is a strange child, serious and clever beyond his years, and he is burdened with an extraordinary supernatural power: when he touches the hand of another person, he sees visions of their deepest fears. One day, Abel is summoned to Constantinople on a dangerous and secret mission related to his clockwork inventions. When he doesn't return, young Zachary is determined to find out what has happened to him - believing his father to still be alive, Zachary sets out on a daring rescue mission across the globe, armed only with his unsettling gift.

It feels almost as though each of Lusk's ideas - a clockmaker's son, the power of seeing people's innermost fears, a rescue mission to Constantinople - could suffice alone as a concept for a book! Each is so unique and so inventive, but remarkably the book didn't feel overstuffed with jostling ideas: it actually hung together very well. This is partly because Lusk's fiction is rooted in a real historical zeitgeist: as I discovered from the historical notes, 18th-Century Turkey did indeed have a fascination with English clockwork automata, and they frequently imported inventions like Abel's. What a fascinating connection that Lusk's story has brought to light - it's a singular and exciting niche of historical fiction.

My favourite thing about this book, however, was not its concept. It was the characters. They were so well-drawn, with such particular mannerisms, pet peeves and inclinations, and such thoughtful, human motivations, that they were all utterly believable. I expect that Sean Lusk could readily tell you the backstory of every character in this book; they were written with a richness that suggested they had lives beyond the pages I was reading. They were also fantastically quirky. There was the overbearing and eccentric Aunt Frances with her menagerie of unusual pets, the fiery, no-nonsense wet nurse Grace Morley and her fractious daughter Leonora, the sparky inventor's assistant Tom who is actually an aspiring young woman masquerading as a man to advance her career... All were endearing in their own ways, and whenever they took over the narration for a chapter, they each had such a distinctive voice. Really good writing.

The only bit of this book that didn't convince me was the romance. Zachary meets his love interest, Ibrahim, in Constantinople; they fall in love and then become separated by circumstances, and Zachary yearns to see Ibrahim again. Although the emotions were written compellingly, I didn't feel I knew Ibrahim quite well enough for this to be fully effective. Zachary doesn't meet him until well into the second half of the novel, and their relationship develops very quickly. For me, this resulted in the sense that Ibrahim's character was slightly under-baked in comparison with the many other dazzlingly whole characters in the book. There were other characters that I loved more deeply, that I could imagine more clearly, and whose loss I felt more keenly than Ibrahim's. So although the relationship itself worked, I wasn't moved as much by this element of the book as I perhaps could have been.

Fortunately, the romance was not the whole point of the novel. Yes, it was a coming-of-age story of a sort, and the first love was central to Zachary's self-discovery. But this wasn't really a book about Zachary finding himself: it was about him finding his father. The whole book explores and critiques parenting: through the absence of Abel, and the parent-figures of Aunt Frances and Grace Morley, Lusk paints a picture of how hard it is to parent a child - how impossible to get it exactly right, even when you love the child dearly. Thus, the relationship in this novel that we most long to see restored is that of Zachary and his father. Parent-child love drives the whole story, and tugs the heartstrings very effectively.

I half-considered interpreting the clockwork in this book as symbolic. Was Lusk doing something clever with the idea of automata, flashy and trendy but ultimately heartless machinery in juxtaposition with the irreplaceable, lasting, real human connections Zachary craves? And perhaps there is something in this - but I'm going to venture that we actually run the risk of over-analysing. After I finished the book, I reached the conclusion that there was no fancy literary agenda going on here. For all its complex details of character, place and history, this book was in essence a beautifully simple story about a father and a son reconnecting. And that was wonderful.

Overall, this book had sparkling prose and enchanting characters, with a heartfelt father-and-son story at its core. Although in my view its romance was not wholly compelling, I would otherwise highly recommend this charming read.